|

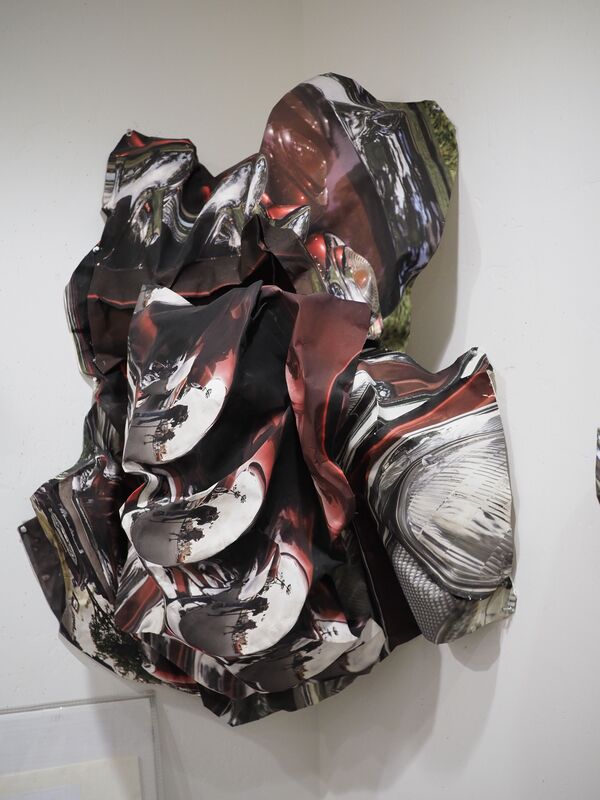

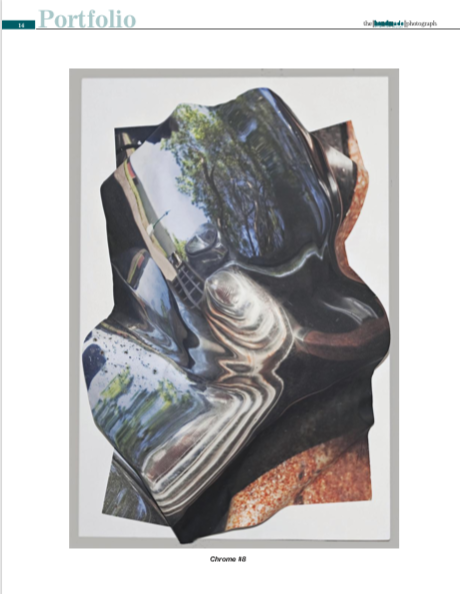

After five decades of abstract drawing, metal sculpting, bronze casting, ceramics and fine art photography - all while raising a daughter and working to support her - Abigail Gumbiner began to sculpt paper. She traveled the country for years, capturing thousands of abstracted photographs at classic car shows, finding the reflective memories of her childhood in the slick paint and polished chrome. She then selected specific images, printing them in her studio on heavy fine art paper. She devised a method of shaping the images three dimensionally to further illuminate the abstractions in her mind's eye.

|

|

Roadside Attractions: On the (Heavy Metal) Work of Abigail Gumbiner

-Andrew Berardini Light curls off the surface of chrome. The gleam invites a finger to trace along its streamlined skin, like wind whipping around a hotrod on the highway. Mirrored metal is a specialty of the American auto-industry, but chrome reflects the country’s industrious speed and its love affair with all machines. Chrome is shorthand for chromium plating, a way to give metal a little protection from the weather. Its shine coated just about anything we wanted, beckoning us. The Airstream took chrome to its automotive zenith, covering trailers and RVs in mirror, but chrome winked from every car for a generation - a shining complement to the new highways that ribboned post-war America and the transience that came with it. The Great Depression may have opened roads to a flood of fortuneseekers and Dust Bowl refugees, but it was President Dwight Eisenhower who made the American highway system an unbroken, open road to every corner of a sprawling nation and the automobile the only way to travel them. Shining off the endless cars assembly-lined out of Detroit, chrome mirrored back the epic landscape and of course the faces of their owners, polished to a perfection you could almost eat a drivethru burger off. Artists were paying attention the whole time. Some squelched and dripped paint, trying to pigment match this country’s new speed and politics that survived the war, invented the bomb, and babyboomed their way through a century that had its name written all over it. Others found the new materials of modernity a more appealing palette than oils and acrylics, and metal-benders from John Chamberlain to Richard Serra wanted to make this newly everyday industrial material sing with aesthetic magic. In her formative years, the artist Abigail Gumbiner (b. 1940) found herself a rare woman with a penchant for making metal shape who turned to her heart’s desires. Studying at UC Berkeley, California College of Art and the Boston Museum School (now Tufts), she received a BA in art, continuing post graduate studies at the UC Extension in the Bay Area. Though her ranging interests took her through many mediums and movements, its her penchant for the American highway and onward to its cars that defined the last twenty years of her work. Light, reflection, and industry coming together into a sheen that only a driver can metaphysically appreciate. It’s hard not to connect Gumbiner’s photographs of the sunbeaten highway signs and sputtering neons of the heady early days of American highways in her 1999 photography book, Vacant Eden - photographed with collaborator Carol Hayden -, to her last dynamic body of work of sculptured photographs. Gumbiner took the speed and crash of the American automobile, the kind Chamberlain liked to crunch into his particular sculptures of crashed cars, and summoned their shine into the medium of light: photography. But it wasn’t the metal itself that caught her attention precisely in this work - it was the light that shivered and bent and beamed from its surface. Peering at the shine coming off cars from its surfaces, I can imagine Gumbiner trying to capture a thousand angles of light into a single photograph, sculpted in radical new ways that could truly embody the multidimensional gleam of metal. She handsculpted her photographs of 1950s cars into dynamic shapes, capturing the energy and momentum of a moment of history to its crashing conclusion. I can easily see in her work the visual appeal of seeing it from all angles at once, and perhaps the warping of reality that this new world brought to its denizens, motoring across America with speed that gave the word ‘horsepower’ heat that no galloping hooves could ever hope to match. In the slants and curves of her late sculptural photographs, you feel all the shine of American optimism, a unique appreciation for the properties of light in a chromed world, and, for me at least, how the speed and industry bent us to its force. You feel all that energy from all those angles and understand the way American heavy metal drove us into the future. And though Abigail Gumbiner has physically left this world, her spirit is still driving with us down the endless highways, camera in hand, winking at us from every shimmer of chrome. |

Abigail Gumbiner is the cover artist in Handmade Photograph Magazine

|

|

Proudly powered by Weebly